VCU researchers want to develop better tools to help diagnose millions of patients with liver disease

The study is funded by a $2.87 million grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

June 27, 2023 Upwards of 10 million people in the United States are affected by a form of liver disease called metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASH, formerly called NASH). (Getty Images)

Upwards of 10 million people in the United States are affected by a form of liver disease called metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASH, formerly called NASH). (Getty Images)

By A.J. Hostetler

Researchers at the Stravitz-Sanyal Institute for Liver Disease and Metabolic Health at Virginia Commonwealth University hope a new five-year study will help them develop better diagnostic tools for patients with an aggressive liver disease that is a leading cause for liver transplantation.

In patients suffering from metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASH, formerly called NASH), a build-up of fat in the liver damages cells and causes inflammation.

MASH affects 3-5% of Americans — upwards of 10 million people — with increasing rates of obesity and diabetes fueling its growth. That’s too many people to make biopsy, the traditional method, a viable screening option for everyone. Many individuals with fatty liver disease feel no symptoms. Given MASH’s silent nature, between 20-30% of MASH patients develop cirrhosis, an advanced form of liver disease, before they are diagnosed.

“Currently, physicians have little to help them identify which patients with MASH and cirrhosis are at risk for a sudden and possibly catastrophic deterioration in liver function. Only when the liver is very damaged can we physicians identify these patients and treat them,” said lead investigator Arun Sanyal, M.D., professor of medicine at the VCU School of Medicine and director of the liver institute.

Without treatment, MASH may progress to a point where the buildup of fat in the liver causes inflammation, scarring and full-blown cirrhosis, permanently damaging the liver, often to the point where the disease is so advanced that a transplant is the only option.

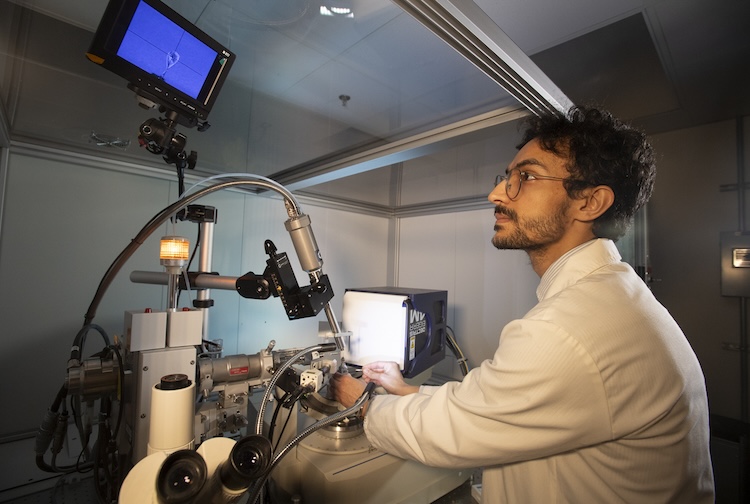

Sanyal and colleague M. Shadab Siddiqui, M.D., a liver specialist and an associate professor in the School of Medicine’s Department of Internal Medicine, lead a new study to find other options. They will combine blood-based and imaging tools to determine if individuals with advanced MASH are getting sicker and develop a predictive model that will allow physicians and their patients to take preventive measures before that happens.

“We hope this will lead to a paradigm shift in how we care for our patients,” Sanyal said. “Whereas in the past we waited for bad outcomes to occur and then tried to prevent further worsening and death, the development of predictive models will allow us to identify who is approaching a clinical event and proactively intervene to prevent the event.”

“Our ability as physicians to identify the patient with MASH cirrhosis who will have a bad clinical event in the near future is lacking, thus limiting our ability to implement strategies to mitigate this risk,” Siddiqui said.

Reflecting on the first year of the VCU liver institute.

In collaboration with Houston Methodist Hospital and Mayo Clinic, VCU Health will serve as the lead site to develop multimodal imaging in an effort to identify MASH patients, whose livers are scarred but still basically functioning, who are at risk for severe liver damage, including possibly liver failure. VCU Health began enrolling patients in April. The research is funded by a $2.87 million grant from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

The researchers hope to show how tools based on existing technologies, such as MRI and ultrasound, can improve patient care by incorporating them into clinical practice procedures to identify new holistic biomarkers. These methods could be used to develop a risk score to better predict acute liver deterioration.

The study will also aim to incorporate these novel biomarkers and models to monitor how the disease might change over time. The overarching goal will be to improve patient care by translating science into actionable clinical practice.

“By providing a method for identifying risk in those with MASH or cirrhosis that can be incorporated into clinical care, we hope this will have a strong positive impact by improving individual patient care, drug development and optimizing care delivery by identifying the population who will benefit most from therapeutics,” Siddiqui said.

While no drug is approved to treat MASH, there are a handful of drugs in development. Sanyal is among the researchers worldwide studying drug candidates to treat millions of patients around the globe. A few potential treatments are expected to seek approval from the Food and Drug Administration in the coming months.